The Anchorage Press Is Dead: Far From Its Roots

The Anchorage Press, as it existed under the tutelage of its original management, is dead. The gritty, street-wise alt-weekly that once was has turned into a soft, uninspired weekly newspaper that mishandles its advertisers and alienates its freelancers.

The Anchorage Press Is Dead: Far From Its Roots

Words / Cody Liska

Photo / Jovell

The Anchorage Press, as it existed under the tutelage of its original management, is dead. The gritty, street-wise alt-weekly that once was has turned into a soft, uninspired weekly newspaper that mishandles its advertisers and alienates its freelancers. It no longer adds to or pushes Alaskan cultures because it doesn’t understand them, and makes no attempt to. Its current management is responsible, not its contributors or its longstanding ad reps. Its current management stands on an upturned bow aimlessly paddling air, the stern is flooded and the ship is destined for the bottom of the ocean.

I wrote that on March 24, 2017, the day I was laid off as editor of the Anchorage Press. At the time I was bitter, mainly because Press Staff Writer Ammon Swenson and I could see positive changes in every new issue of the paper. We were pushing it in a direction that elevated its freelancers and spoke to a multi-media generation. Our pool of talented, reliable writers and photographers was growing every week and we were strengthening those relationships with monthly meet-ups—what we considered a semblance of a newsroom. Great ideas came from those meetings, ideas that later became thoughtful articles and themed issues of the Press. We had a lot going on and for it to be cut off so abruptly was shocking. Ultimately, everything was too fresh for me to write about it with the perspective that comes with hindsight. That’s how I found myself, over the course of three months, interviewing a slew of Press alumni to see what that perspective looks like.

“What do you wanna know,” Anchorage Press co-founder Nick Coltman asks me from across a table at his newest venture, Indigo Tea Lounge. My answer wasn’t simple. I wanted to know about the early years of the Anchorage Press—the Golden Years. Back when Robert Meyerowitz was the editor; back when Chris Ridder pissed off the Hells Angels; back when Susy Buchanan retraced the path of a murderer one winter night. I wanted to know about prostitutes lining up to pay for ads; I wanted to know about the Anchorage Bypass, before the paper was renamed the Anchorage Press. But mostly I wanted to know how the paper, in all its shaky existence, went from what it was, to what it is now.

“The selling point that [the Anchorage Press] had was the localness of it,” Nick tells me. “Readers are not looking for [the Press] to talk about national politics. There might be a national issue which we can sort of drill down on locally and make it interesting to readers, but it has to be Anchorage first. Local music, local restaurants, stuff that matters to the people who actually live here. That’s the most important thing, that and being a part of the community—that’s what I see the [Anchorage] Press not doing right now.”

Co-founders Barry Bialik and Nick were in their late twenties when the first issue of the Anchorage Bypass came out in September of 1992. Barry was the first editor. He and Nick knew each other because they both had previously worked for Rural Alaska Newspapers. “We had no experience in starting a newspaper, but the Anchorage Times had just closed and we saw an opportunity,” Nick tells me, “There were three or four other groups [that] saw the same opportunity at the same time, only one of them got one issue out and we’re the only ones who made it.” Almost immediately after they started the Bypass, Nick took off to Ecuador for a 4-month climbing trip he’d scheduled before all this talk about starting a newspaper. He didn’t expect the paper to still exist by the time he got back, but it was. “They didn’t have sales, but they did have some sales staff,” he says, “Barry and Bill [Boulay] were really committed to it and they got a bunch of volunteers in the community who were committed to it too. So, I jumped in and started doing sales full-time.”

It was about a year later, in 1993, that they renamed the Anchorage Bypass to the Anchorage Press. In the early years of the Press, they weren’t hoping to get rich, they were just happy to get concert tickets, free beer and to be out partying all night. They were young and ambitious, guided by passion and purpose. And so they did everything themselves, from gathering editorial to sales. “We’d stay [at the office] all night to get the paper out, then we’d go deliver it ourselves,” Nick tells me. “Then we’d do the invoicing. And then we’d do the next paper. It was like 36-hours straight sometimes… Maggie [Nick’s wife] did all the books and the invoicing. She typed up all the classifieds. She was really hands-on…[Her] masthead read ‘Everything Else’… It was like a family owned business… Everyone was really passionate about it. We all ended up living in the same house because Barry had a house and everybody else was out of money. We didn’t take a check for two years. So, it was passion in the beginning.”

The Press at Koots / Courtesy of Nick Coltman

It was hand-to-mouth until they landed a military contract with the Elmendorf Air Force Base newspaper, the Sourdough Sentinel, in 1994. “In the Air Force, you can have PR people who write and take photos and do things like that, but they don’t have sales people,” Nick tells me. “It would be funny for a military guy to try and sell advertising, so we took care of the printing, the sales and the distribution.” That contract gave the Press the financial stability to keep going. Years later, in 2005, Elmendorf Air Force Base merged with Fort Richardson and became Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER). The Sourdough Sentinel was eliminated and a new paper was created to represent JBER, the Arctic Warrior. That contract still remains with the Press today, or more accurately the Press’ parent company Wick Communications.

In the fourteen years before Nick sold the paper to Wick in 2006, that’s more or less how things went. Nick built-up the Press, as a sales rep at first and then later as publisher. There was a publisher who came on a few years after Nick left—six months after he sold to Wick—who had no business being at the Press, Nick says. “[He was] super conservative, Knights of Columbus guy. [He] wanted to change the paper completely. He would go into businesses and say, ‘we’re really going to clean up the Press and we’re gonna make it a community newspaper.’ That’s never gonna fly. You’re alienating your readers and you’re going into businesses and saying, ‘you should advertise in this paper I don’t like, but I’m going to change it.’” The current iteration of the Press is repeating history: its new management is attempting to remake a paper that, in its heyday, thrived in its pursuit of immersion journalism. Be it a metro feature or an arts and entertainment profile, back then the Press was telling stories that no other publication in Alaska could.

Nick has stories, too many to count. At one point a woman named Cheryl sold classified ads for the Press and she’d yell at prostitutes on the streets, saying, “Don’t walk the street! Advertise in the Press!” Prostitutes would line up at the office to pay for ads with cash. “If they didn’t make it by deadline, they’d be pissed,” Nick tells me. “Other than walking the street, it was the only way for them to get customers. Now it’s all Backpage and Craigslist.” There was also the time Chris Ridder wrote an article about transvestites in Anchorage and, in a throwaway line, said that you never know who might be wearing woman’s underwear, it could be a businessman or a Hells Angel. “The Hells Angels came to the [Press] office—we could hear their engines from all the way down the street,” Nick tells me. “The guy’s name was Tiny, he was about 350 pounds and he filled the doorway. He was like, ‘if I get one pair of panties in the mail or I hear about this again, I’m coming back here.’” An apology to the Hells Angels was printed in the paper the following week.

The success or failure of a publication hinges on good sales people. Nick can’t emphasize that enough. “If you’re not bringing in money, you can make the best product in the world, but the printer is not going to keep printing it without a check,” he tells me. And Nick could sell. In fact, the reason lauded Press editor Robert Meyerowitz took the position was because he went on a few calls with Nick and saw him sell the paper. “I thought, ‘well, he’s really good at that,” Robert tells me. “If he can sell it, I can build it.’” Because of the public perception of weekly newspapers—that they’re comprised of screaming liberals and callow youth—Nick wore a suit and tie to meetings. He knew the paper inside and out; he believed in it and he had the pitch to prove it.

The first two major advertisers that ran in the Press—the ones that opened the flood gates for other advertisers—were Oaken Keg and Chilkoot Charlie’s. “I think having Oaken Keg and Koots gave us some respectability and credibility with other businesses in the community,” Nick tells me.

Before Nick sold the Press to Wick, ad revenue was on the rise, he says. “I guess that’s the thing that annoys me, we were pushing $1.75 million a year in sales and I thought that with Wick we should get to $2 - $2.5 million, but it went the other way.”

Robert believes that Wick’s purchase of the Anchorage Press was the first deathblow to the paper. “The beginning of the end was when we sold the newspaper to Wick… I don’t know what Wick thought—maybe they thought [the Press] was going to be this little moneymaker, and it has probably disappointed them? I don’t know. I don’t think that they had much regard for the thing they bought in terms of the content. We were kidding ourselves if we thought they liked it the way it was and they didn’t wanna change it. They stripped it down and when they had to hire people, they brought in new people from Outside, from Wick, who didn’t know what the paper had been before yesterday and didn’t give a damn. And that does real damage.”

Before Robert came to Alaska, he was a foreign correspondent for NPR and the Associated Press. In 1994, he moved to Anchorage and worked as a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News for three years before he started freelancing for the Anchorage Press. He did that for about a year before he became editor. During his editorship at the Press, the newsroom was as big as it ever would be. Thirteen people in total, all working beats and producing solid content.

Robert Meyerowitz's Anchorage Daily News ID badge. / Courtesy of Robert

“We were getting a lot of attention,” he tells me, “people were reading us, we were connecting with the Anchorage community. There was a scene around that newspaper then and we were all a part of that… We put on events, we started contests—the Haiku Poetry Contest, the Super Short Story Contest and the Post-it Art Contest. It had this great vibe, you know? The people who worked there, they loved working there and they acted like they would’ve worked there for free because they just loved being a part of this thing… I doubt the people who run that paper nowadays, especially the business side, feel as good about what they’re doing as we once did.”

There was this idea back then that the Press was The Little Engine That Could because they were the underdogs. A lot of that was established through trust, Robert says. “We were taking a chance on the people we hired and those chances paid off because we trusted them,” Robert tells me. “This is what newspapers do when they’re good weeklies: they give you a sense of place, they give it back to you. You see the place you live in through the eyes of the people who are doing those stories and taking those pictures. And it tells you something about where you live and it helps shape an identity about what it means to live here… You don’t have to be from [Alaska] to do that, but you need to be invested in it and experience is crucial to that… You can’t just AstroTurf it and put stuff in that paper that could just as easily run somewhere else. It’s gotta be locally generated. It’s gotta be organic that way. Otherwise people know.”

When I ask Robert to recall a memorable story, one sticks out above the rest. It was about a group of crabbers who would, on their days off, go to sea lion rookeries and “blast the shit out the sea lions, killing as many as they could.” The story was called “Killing Sea Lions” and it was written by Toby Sullivan in 2005. On the cover of the paper, there was a blurred photo of a sea lion that looked like it was drowning. There are still people who second guess Robert’s decision to publish that story. “That brutal description of killing these animals for no good reason, it was an important story,” he tells me. “In some ways, it was more than anybody wanted to hear. And that’s a good thing for a newspaper to do. You’re not going to please everybody and you might as well risk upsetting people if you believe in the story.”

At least twice in our interview Robert emphasizes that a newspaper doesn’t succeed on its own and that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. That without its staffers and contributors, there would be no Press, let alone a Golden Age. “Tataboline Brant, who went on to work for the [Anchorage] Daily News. Tony Hopfinger, who went on to start [Alaska] Dispatch and then takeover the Daily News. Amanda Coyne, who started Dispatch with [Hopfinger]. Jessica Rinck, Renee Baranov. All those people, they remember that time, that golden time, in the early-2000s, of the Press as a real highlight in their lives. I’m speaking for them, but I think they would tell you that. We were all working together toward this thing. They believed in the paper, they believed in Nick. Nick was a great leader in a lot of ways—not a leader in the sense of more return to the investor, but reinvesting into the paper.”

Nick Coltman / Courtesy of Renée Baranov

Lynne Snifka singing for her Muskrat Love story. / Courtesy of Robert Meyerowitz

Tataboline Brant Enos / Photo courtesy of Robert Meyerowitz

According to David Holthouse, the Press was at its best under Robert. Cautious to not devalue the efforts of other former editors of the Press, David says that while Robert was a talented editor who devoted his life to the paper, he also had the benefit of large budgets which allowed him resources and a large staff. To do that job right, David says, it has to be your entire life, and it was for Robert. “Robert would last about 30-minutes under the Press’s current management,” David tells me. “I didn’t expect you to last more than three weeks.”

David first became aware of the Press in the summer of 1994, back when the paper was young and beginning to gain some recognition. He was working for the Anchorage Daily News then, doing investigative pieces and writing about music, when Barry cold-called him and asked if he was interested in jumping ship. He was intrigued enough to go down to the Press office and rap with Barry and Nick about it. “I kind of just wanted to go over there and pay my respects and tell them I appreciate what they’re doing,” he tells me. He didn’t end up taking the offer, though, because he was already thinking about taking a job with New Times out of state.

There was something else that happened during that first meeting between David, Barry and Nick—a leak. At the time, the Daily News was getting ready to launch their weekly entertainment paper, 8. A prototype was printed and, for some reason, David had it with him. “I was talking with them and I basically spilled the beans,” he laughs. “I showed them the prototype and I was like, ‘you guys can’t do anything with this.’ And in next week’s fuckin’ Press there’s this big article about how the ADN is getting ready to launch this competitor to the Press. They didn’t dime me out, but it’s clear they’ve seen the prototype. And the ADN launched this internal investigation that I had to sweat out.”

The outcome of that first meeting didn’t sour David on the Press. In fact, in 1997, he began writing for the paper under Robert. “That’s when I really became involved with the Press,” he tells me. David went on to become one of the most recognizable voices in Press history. One ad rep told me that “when David had the cover, papers would fly off the racks.”

When I ask David his thoughts on the 2006 sale of the Press, he echoes Robert’s opinion: “I would put the beginning of the end at selling the paper to an Outside company. I don’t fault [Nick] for that. It was a smart business decision. At the end of the day, Nick is a businessman, not a journalist. He’s just a businessman that understands good journalism… Wick or no Wick, it came down to whether or not Nick was the publisher. Nick’s the kind of guy who understands that content drives revenue. That’s another fundamental disconnect right now. I feel like [when] Wick is left to its own devices, they just wrap words around pictures and ads. I don’t think they understand that quality journalism is what gets people to pick up the paper.”

“It’s always been a fuckin’ rollercoaster,” Brendan Joel Kelley says of the Anchorage Press.

Brendan wrote his first article for the Press in 1995, he thinks. It’s easy enough to find out because it was an interview with Fugazi. They’re notorious for refusing interviews, Brendan says, but he knew Ian MacKaye so he was able to set it up. It’s a funny story actually, how Brendan knows Ian. When Brendan was 14, he wrote Ian a fan letter, Ian responded and soon they started writing postcards back and forth. At that time, a lot of editorial was done out of editor Jordan Marshall’s apartment. There were old Macintoshes on the floor and that’s where Brendan edited the Fugazi interview. That was his introduction to the Press.

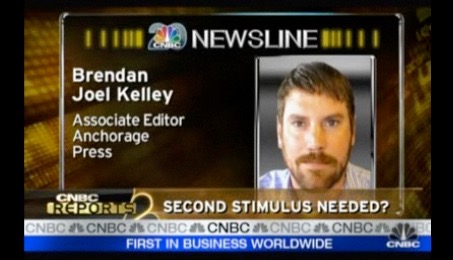

The following year, Brendan went to work for the Phoenix New Times. From 1996 to 2007, he worked there and at its sister paper in Ft. Lauderdale. In 2007, he got word that the Anchorage Press was looking for a staff writer. “Holthouse said, ‘you should absolutely do it because you can write your own ticket, you can do what you want,’” Brendan tells me. So, he interviewed for the position and, without knowing if he got the job or not, moved back to Anchorage. Shortly after being hired on as a staff writer, he became Associate Editor and then in 2009, when Krestia DeGeorge left, Brendan became editor.

Brendan with Sen. Ted Stevens, sometime during the 2008 senatorial campaign (which he lost to Mark Begich) / Courtesy of Brendan

“The single biggest phenomena that we went through and participated in and had to find our role in [was when] John McCain announced that he had chosen Governor Sarah Palin to be his running mate,” he tells me. “Being a dinky ass, little newspaper, no one knew how to deal with The New York Times and The Washington Post on the line asking us for people’s phone numbers and who to talk to. That continued throughout the campaign, right up until Sarah [Palin] quit on July 4, 2009.”

Screenshot from Brendan's CNBC appearance. "The funny part is they Photoshopped out my earrings," Brendan says, "and ADN’s gossip column, the Alaska Ear, wrote about it with side-by-side images of what I’d given them and what appeared on screen." / Courtesy of Brendan